The Case for Care

by Ellie Zupancic

Photos by Vivian Le

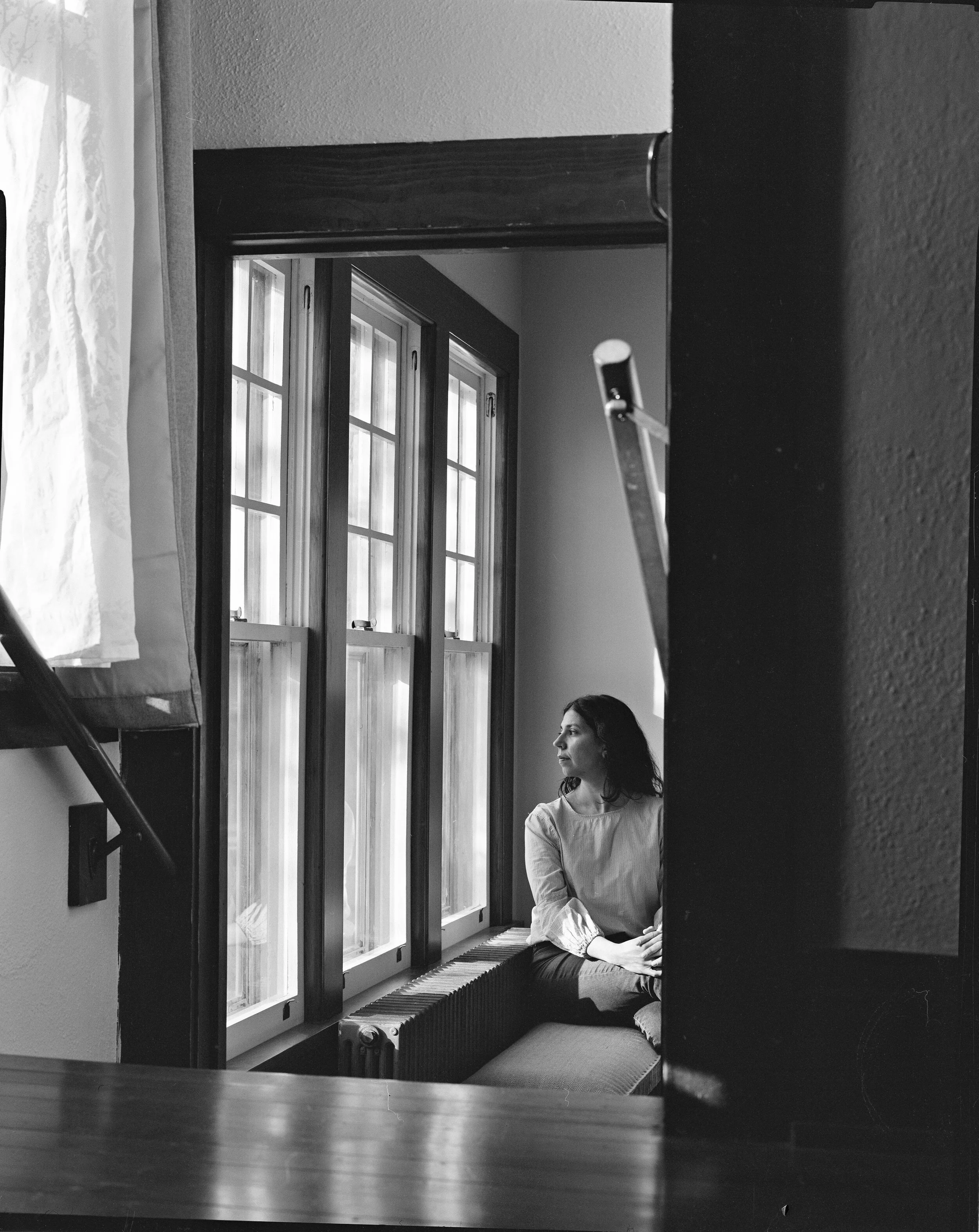

Philosopher Asha Bhandary

has created space for self-discovery, personal priorities, and thought—to develop the most robust account of dependency care in a liberal theory of justice.

Asha Bhandary began working on the paper which became her first article, and later the basis for her book, in a graduate seminar—around the same time she went on a spring break trip with her husband. On a Saturday afternoon, we sit in her living room awash with light, and as she recounts the story, her tea kettle starts to whistle. She gets up from the couch, still talking as she makes her way into the kitchen: “We went up to Montreal, and I was working on the paper there. Eventually I said, ‘I’m not getting enough work done!’” her voice intensifying and quickening, “‘We just have to leave,’” and so they drove back home. I wonder if she threw up her hands as she said it.

Bhandary is a political philosopher and feminist ethicist whose most recent work centers around care. I first encountered her during my sophomore year at the University of Iowa, in a course called Multiculturalism and Toleration. At the time, I hadn’t anticipated the transformational force of the class which ultimately helped me carve an interest in feminist philosophy, in the philosophical discipline as a whole. It was a force strong enough to situate me where I am now, a year from graduating, with plans to pursue a higher degree in philosophy after Iowa.

A day before approaching her newly-renovated and light-struck craftsman home from the early-20th century, I sat in the English-Philosophy Building on campus for one of the faculty colloquium events hosted by the Department of Philosophy. I was already familiar with the work of her last book, Freedom to Care: Liberalism, Dependency Care, and Culture (2019), as well as insights to forthcoming papers and projects. However, what I ended up hearing there was new. Her argument for interpersonal reciprocity was, to me, a powerful one that hit close to home. She framed the concept as an ameliorative virtue, something vital to a theory of distributive justice; that is, a virtue which can address the inequalities and injustices in the domain of dependency care (intensive, hands-on care, without which a recipient could not survive–such as care for an infant, an elderly person, or a disabled person). Interpersonal reciprocity in the real world looks a lot like what it sounds like: the sort of reciprocation that happens at the individual level, that isn’t rooted in any idea of exchange which would change one’s motives. There’s something about the self which must be left behind in this way; when we refuse the mindset of exchange, we both act on an impulse born out of a regard for the other and come upon a safeguard, by way of the expectation to reciprocate, against sedimented racist behaviors. This concept doesn’t preclude other caregiving practices in the world, but to Bhandary, the virtue of interpersonal reciprocity is one we must cultivate in the mainstream U.S.

Before being welcomed into the living room of her Iowa City home, I wonder how she’s gotten to this place, to care. We situate ourselves on two couches and she reflects on her undergraduate education at Stanford where she was editor for an English journal. “I wrote an article about Sylvia Plath. When I look back on that now I see that I was thinking about things in terms of distributive justice.” Bhandary realized by reading her poetry and learning about her home life that Plath needed more support with her children, “because she was a great mind, and she was being stifled by her husband. He wasn’t providing the material support that she needed, so she stuck her head in the oven. Of course, there’s so much richness in her writing but I was really thinking about these material distributions and their relevance.”

When Bhandary decided to become a mother, she was in graduate school at 28 years old. She was writing her dissertation, then, under the guidance of Diana Tietjens Meyers, newly going through the world as a mother. She learned very quickly how peoples’ expectations shift after inheriting that status: “People would smile at me so warmly when I was with [my daughter]; but if I was off doing something else, there was a very noticeable friction.” I think of the mother as having a layered consciousness, like living two lives: existing at once in a public and private domain under the ‘mother’ label, forced to internalize new consequences and sacrifices within both. “My husband was also a resident at the time, so I was basically raising her alone for her first three-and-a-half years. I came to know what dependency care involves in that way. That social position has definitely made me a much more informed theorist about care.” Still, to Bhandary, motherhood has felt less about sacrifices and more about the process of becoming clearer on what’s truly important; in thinking about care on a broad scale, she identifies the prime moral hazard of writing such theory: “To betray love.”

In a brief interjection, her oldest daughter runs back in from the front yard and asks, “Mom, can I take my hairclip out? It’s falling out.” Bhandary responds: “Clippy? Can I fix it? Here–” and again is up.

I am immediately reminded of the role I often took–growing up a middle child but nonetheless playing the part of big sister. There’s a sly way in which the older sister takes on a sort of motherhood figureship, even in families where the mother is present and adequately caring, even when there are additional siblings. I remember Bhandary’s interpersonal reciprocity again; how my mother has spent a lifetime caring unceasingly as the oldest of five siblings, as a practicing nurse, as the mother of three children; how it only ever felt like love. I wonder how many times my mother performed the stowing-away of herself as part of the expense of being a caregiver; and I remember her sitting me down last year after thinking about rewriting her and my father’s will, telling me I would be listed as the primary caregiver of my sister–whose cognitive and emotional disability will require some form of care for her life–in any circumstance where they no longer could. It sounded, to me, both like the right choice and the choice I feared most.

I remember Bhandary’s interpersonal reciprocity again; how my mother has spent a lifetime caring unceasingly as the oldest of five siblings, as a practicing nurse, as the mother of three children; how it only ever felt like love.

Bhandary recalls growing up in the sibling-position opposite of me, having an older sister. She explains the second personal cognition that older siblings have, how they must think both about themselves and the sibling–the younger free to do what they will, always retaining a sense of being cushioned in the world. “It’s interesting to see my two girls now, my youngest living so free in the world, knowing, in a way, that the other will catch her,” she says. The two girls are still coming in and out of the home, this time in helmets, planning a bike ride around the neighborhood with their dad, Bhandary’s husband of 14 years.

“When I was growing up, we travelled a lot. I’d visit India and Finland every few years where our families live, so I was familiar with different societies.” It makes sense that observing how different social, cultural, and political arrangements affect people’s lives has animated Bhandary as a political theorist, as someone working on a theory of justice. Still, she is quick to acknowledge the part of herself that, if there were no social injustices in the world, would just as easily devote time to studying ants or plants. Her voice slows down when she mentions it: “Moss is so fascinating to me. It has sporophyte and gametophyte phases; it’s one creature in the first stage, and a different creature in the other,” and then she returns to her typical, thinking tone: “But there are clear problems of social injustice that we need to address. And, really,” her voice shifts, like she’s letting me in on something, “I think we probably could. I think it’s within human capabilities to address some problems that are very straight forward.”

Vivian Le for Fools Magazine

“…there are clear problems of social injustice that we need to address. And, really,” her voice shifts, like she’s letting me in on something, “I think we probably could.”

Care in the philosophical world isn’t necessarily what it’s made out to be in mainstream discourse. In Bhandary’s book, Freedom to Care, self-care is intentionally excluded. The term itself has swiftly come to signify much more than fundamental nourishments of oneself and one’s life, yet it differs greatly in its aims and requisite skills from those for dependency care. I’ve found myself over the past few years treating self-care in a very capitalistic way, buying into the idea that if I pay for candles, face masks, essential oils, and then dim the lights and sit in these things, then I’ve somehow achieved self-care. It’s a distinctly Millennial- and Generation Z-form of self-delusion–not just by getting in on the practice, but by its being situated in our laps as consumers, by the way we can’t resist the thing in our laps.

Bhandary’s work, though, is more concerned with the practical implications of writing a theory of justice–like the ability to address exploitation in care when it happens. Part of this means acknowledging that there’s something substantially significant required when caring for someone else. Part of that significant thing is pushing the self out of the way–suspending one’s own interests and needs in order to care for the other person. This orientation is vastly different from the one required for self-care. Care, then, by Bhandary’s terms, is essentially other-directed–other-directedness meaning the “attitudinal, motivational, and perceptual orientation towards the needs and perspective of another person.” Nonetheless, Bhandary doesn’t depart entirely from notions of self-care in her personal life. She identifies things important to the concept such as knowing one’s own needs, what nourishes oneself, and what one values. “Part of self-care for me is detecting which people I feel good around in the personal domain,” she says, “acknowledging that we all have limited time–and tracking what matters specifically to me.” In this way, Bhandary can have her trip to Montreal, and leave it, too.

“I’ve been thinking recently about how I’ve had an evolution as a woman of color, but specifically as a woman of color in Iowa who is also a mother,” she says. I start to think the transformation from woman to mother marks something similar to moss, birth being the “ring of fire [Bhandary walked through and] came out the other side of.”

In this way, Bhandary can have her trip to Montreal, and leave it, too.

In speaking about her pregnancy and childbirth experience, Bhandary returns to the idea of self-abnegation, or leaving the self behind, which she says “has more to do with the way basic needs are postponed when you’re caring for someone who’s dependent, who gets the moral priority. In the process of pregnancy and childbirth, you learn that in a very physical way.” There’s some sort of violent process by which the child is going to come out, and one’s body will tell the story. A second loss experienced in childrearing is the weaning of the child from nursing, she says: an overwhelming bodily and hormonal shift which breaks two bodies, once together, apart. I understand, then, the corporeal self as a sort of constant, whether in the morphology of moss, the process of childbirth, the weaning of an infant–the physical body remains. Perhaps scarred or transformed, or nearly recreated anew, but the body remains nonetheless.

Before ending our conversation, I redirect us towards the philosophical notion of autonomy–something I’ve been working on over the past year in anticipation of defending my honors thesis under Bhandary’s mentorship. Bhandary grapples with autonomy as a political concept in Freedom to Care, intended to meet political goals and ends, not as a personal concept; however, developing a personal account of autonomy is part of her big next-book plans. What she stands by now, in a developing line of research, is a way of thinking about autonomy and distributive justice in the context of understanding people as physical beings, who are in a physical world, who are affected by various things. We are also relational selves, according to Bhandary, meaning we understand who we are based on our relationships with others and the consequent understanding of how we stand in comparison to them in the world. But, Bhandary revises, “we are dynamic–not relational in a fixed way. People can recover from trauma. People can recover from relationships which change or end.”

Vivian Le for Fools Magazine

If Bhandary were to summarize a view on autonomy, “it would be the basic idea of living a life that’s guided by your values and convictions. Doing so requires different abilities in terms of understanding the social environment and the friction you might receive for doing certain things or making decisions about how to do what you want to do.” Bhandary notices these dynamics in her own life, too, paying attention to things she does that might “annoy” people. Refusing to be interrupted is one–and something I presume is magnified by her social positioning in the world, especially in the field of philosophy which remains largely dominated by white men. These observations are how Bhandary got to the liberating point of realizing “there’s no way for me to do what I want to do in this life while pleasing everyone. Sometimes it’s a trade-off–if you play into people’s expectations a little bit, then maybe there’s a reward. But what I’m doing in this life is this intellectual work. It’s this thought. It’s this writing. And it’s not worth it to me to try to please people who are not going to be pleased.”

"…what I’m doing in this life is this intellectual work. It’s this thought. It’s this writing. And it’s not worth it to me to try to please people who are not going to be pleased.”

Accessing her own autonomy came in part by the way Bhandary was raised: “My parents always let me make my own decisions. That ability to think about what you truly want to do is important. When I was deciding where I wanted to go to college, I went for a long walk.” Other times, when she needed to think, she went to a park and sat on a rock. Sometimes something seemed like the sort of route she should want to go, or the sort of activity she should want to do, yet she found something in her just didn’t want it. Conversely, she gestured to the idea that we might be guided toward a thing because of something about who we are, but we can’t identify it at the time. This is part of self-discovery, an impulse worth listening to. Bhandary herself is, in some way or another, always going back to that rock, or hitting the pavement, as the avenue to think. In this way, she sits on the rock, the world made infinitely more cramped and spacious by way of being on top of it, both.

Asha Bhandary’s latest book, Freedom to Care: Liberalism, Dependency Care, and Culture, published by Routledge in 2019, is available from CRC press online.