For Later, When All My Homies are in the Room: An Interview with Hanif Abdurraqib

by Skyler Barnes

I keep writing. Though that’s objectively good I suppose. It’s rainy and fog-laden outside my window and I could have sworn the forecast said there would be light. I sit in my egg chair given to me from a departing friend and stare at the pecking birds outside my window. To be pecking for food and finding it – a dream. I sit here perched in my window ledge watching the inactive street below. Vacant, the world feels. Isolated in our homes are tucked away plans and idle time. Before now the world seemed so tangible. Doorknob squeak and echoed laughter down a hall. My house is creaky, pushed over by visiting wind. The only whispers I hear now are from my own mouth, almost autonomous, almost company. Though, like I said, I keep writing.

Before, in the bustle, I had interviewed Hanif Abdurraqib. I entered his office in the nonfiction essay lounge of the EPB. I was jarred to see him, as if his name were not on the door, as if we hadn’t sent numerous emails, as if I didn’t belong. I think back to that now and the shared breath hitting his office walls. How grand to share a space. Spring break started and ended a few weeks ago and each new rise brings more conflation; the impending sense of doom and the persistent wish for optimism. I attribute this to shock, the in-between space of hysteria and complacency. I also blame the quiet. I remember his recurrent mentions of Toni Morrison, “the greatest black Midwesterner.” I pick up my copy of Sula.

Skyler Barnes & Hanif Abdurraqib (January 30th, 2020)

Odessa Neeley for Fools Magazine

I had asked Abdurraqib about Ohio, but really it became about community, rather it be the “teachers who saw in [him] the potential to be a worthwhile writer” or the writerly friends garnered from slam performances and MTV column writing. I had admitted to him that I found his work first through Button Poetry. It seems like we were both “around 2011, 2012 … writing bad drafts but not really sharing them with anyone,” the difference being he was on the screen that I was sat in front of.

“Slam is almost nonexistent now, at least in the way it was. But I came up with slam during the time where it was a real golden era of writers and performers … Young poets of color who were kind of – largely poets of color, it was poets of color and then Sam Sax.” I laughed. I remember fondly the times I spent regretting not joining my school’s slam club – the one meeting I went to was largely overfilled with talent I thought I did not possess. And yet conversely Abdurraqib was in LA, or St. Paul, or the Rustbelt, or anywhere else with Danez Smith and Franny Choi, and Sam Sax, crowded in someone’s hotel room, reading their best work to each other. It’s in that reciprocity, I imagine, that artifice lies.

It was this semester that granted me with the community of writers that I so desperately craved. Email threads full of poetry and jokes and makeshift readings done in downtown diners. All of these spheres circling and overlapping for moments at a time, a collective Iowan subconscious. Tap into it.

Still, he says, “I really worked in isolation for a long time to build my skillset … I don’t think having a community is required … I think that there are a lot of folks who are averse to it and they do their work just fine … I just do the work and from the work comes more work.”

So, I sit. The wind picks up and my house screams. Somewhere in that cacophony, I hear a nothingness telling me to write. It’s in this isolation, I suppose, that work will birth work.

THE TRANSCRIPT:

Skyler: I’m first and foremost wondering how you ended up here at the University of Iowa as a visiting professor.

Hanif Abdurraqib at Prairie Lights (January 30th, 2020).

Odessa Neeley for Fools Magazine

Hanif: I wish I had a more interesting answer than that; they just asked me. Last year sometime, I think in the spring. They were interested in having me come by. Y’know, I don’t really have any background in academia. It seemed like a good opportunity to kind of, come to a place and kind of learn a little.

Skyler: That leads me to one of my other questions, you mentioned that you don’t really have a background in academia, I’m wondering what you think the role of education is in making a skilled writer.

Hanif: I’m a little more cynical honestly, I don’t think structured education is necessary as much as an ability to self-educate and the ability to have access to ways to self-educate. Be it libraries or bookstores or a pipeline of mentorship that really works for you – I don’t think the structured realm of academia is at all necessary to build a skilled writer. Like I said I have none of that. Y’know, I found a community of folks who were invested in my work and then through that I became invested in my own work and I think I was fortunate enough to live near a library so I had access to books and I was fortunate enough to go to school and have teachers who saw in me the potential to be a worthwhile writer. Point me in the correct directions to do that. But also, I really worked in isolation for a long time to build my skillset. So, undoubtedly academia is useful and provides some of these modes of learning how to write or finding confidence in voice for people, but I don’t think it’s required or necessary.

Skyler: Was that community that you found in Ohio?

Hanif: Yes, yes Ohio.

Skyler: How do you think Ohio impacted how you came up as a writer, other than the community that you found. Did the state of Ohio itself, affect you?

Hanif: I think I’m seeing it more in my work now than I did when I was younger. I think mostly it impacted my strong desire to tell stories that I felt were not being told as rigorously. Just stories of black folks sounded less particularly. So, to grow up in a place where I was around a lot of black Midwesterners and to come from black Midwesterners – and to be in a state where Toni Morrison is from, the greatest black Midwesterner. Jackie Woodson is from Columbus. So there were black Midwesterners writing stories about the black Midwest, and y’know, it was important for me to want to fit into that lineage while understanding that I wasn’t the first, I wasn’t going to make any new ground outside of telling the stories that I knew, which were different stories than Toni Morrison knew or Jackie Woodson knew, or Wil Haygood or any of these other folks. If there’s one way Ohio’s impacted me it’s that, y’know, I think my lens on the world is a little bit different. My concerns are a little bit different; they’re very concerned with unearthing and sharing black Midwesterner stories that I lived through.

Skyler: How do you think – you obviously write a lot about music as well – how do you think music and that cultural scene interacts with that black midwestern archetype?

Hanif: Well, I mean I think that for a lot of those black folks that I grew up with, we felt – we felt like outsiders in some ways, even if we weren’t. I think when you’re young it’s easy to make yourself feel as though you’re more of an outsider than you actually are. Y’know, the punk scene that I found – I was so comfortable with that outsiderness, so me and the few black kids on the punk scene really formed a bond around our abilities to be on the margins – these particular margins. That led to a lot of freedom, I think. Like a lot of unburdening ourselves from expectations of whiteness, the gaze – the pressures put on us to conform because if we were on the outside we didn’t have to conform or be concerned with conforming anymore. I think that unlocked a real freedom for me and my ability to face my people and talk to my people. That’s the main concern.

Skyler: I do have to fangirl for a moment. I’m from Kansas, so I do feel like I get that black midwestern vibe. And I found you on Button Poetry, and that’s how I, y’know. I feel like your writing helped me understand a little bit more of what that black midwestern experience was.

Hanif: What part of Kansas?

Skyler: I’m from Kansas City! Not the Missouri side, obviously, the boring Kansas side. But could you talk more about your Button Poetry days, and the inception of your career.

Hanif: Yeah, I don’t even know what’s on Button Poetry. But I’ve never really been that rigidly affiliated with them other than I came up in slam and they recorded slam. I got into poetry around 2011, 2012, and to push myself to write more poems, which I knew I needed to do, I was reading a lot of poems, I was writing bad drafts but not really sharing them with anyone, and I was doing it with no real discipline. There was a slam in Columbus, it’s no longer there, but the mag is still there, it’s called Writer’s Block, and in order to participate in the slam you had to bring at least one new poem every week, but sometimes two. I got into slam merely to give myself a deadline, because I knew if I wanted to go, y’know it was the only thing that was forcing me to write poems. I needed a practice that would force me to write more poems so that the poems would get better. I could look at them and say okay well, this is working a little better this is not working, or the more I’m writing the more I’m seeing these trends of what I’m good at and how it can lead to more strengths. So really, I did slam because it was a way for me to write poems and y’know, I think the thing with slam is that there’s really no such thing as being good at it. But I did have some success in terms of getting on a couple poetry slam teams and going to national and regional events, and through that I really built a community of writers. I came up with slam. Slam is almost nonexistent now, at least in the way it was. But I came up with slam during the time where it was a real golden era of writers and performers. And I think at that time though I think a lot of these institutions would deny it now, at the time the talk was that all of these like young poets of color who were kind of – largely poets of color, it was poets of color and then Sam Sax – all of these poets of color were dropping into the slam scene were skilled performers, but they couldn’t write. That was the underlining narrative about the work. So, I think that we really formed a bond trying to impress each other and not trying to impress the high and mighty poets of thou. And I think that again goes back to this idea of facing your people and giving people what they want. So that was really important, finding that community made me a better poet because I – I mean there was a point for me and my peers I think where we would go to a national poetry slam and sometimes not read our best work on stage because we’d do this thing where after the slams were over we’d find someone’s hotel room and read each other poems. Danez Smith and Franny Choi and Sam Sax and all these folks. So y’know folks would withhold their best work – like sometimes if you’re on a slam ballot, your homies aren’t in the room. So sometimes I’d be like, well, I’m going to save this poem for later when all my homies are in the room. And that was a really propellant thing for me.

Skyler: Do you think that poetry is more of a community thing rather than a publishing thing? More of a personal interaction?

Hanif: I think it depends on the poet. And I also think there’s a way that those two things that are stacked. I think that I don’t really publish a lot of poems anymore. Y’know in my last book I didn’t publish any of those poems, I published like a few. I’ve gotten somewhat less interested in the private act of publishing poems and more interested in figuring out how I can play a role in helping publishing work for poets across the board. If I can play a role in that at all. But that doesn’t mean that I’m disavowing publishing I just think that, y’know, I’m a big Toni Morrison disciple. A thing Miss Morrison often said was ‘if you got free it’s your job to free someone else.” For me that’s actually a question of how is my continued pouring of work into the world in the same volume that I always had, is that contributing to a scarcity? I did the math on that and found that the answer was yes. There was a point where I was publishing poems all the time because I could have. Surely, I still could publish poems, like, a lot. But there’s something interesting to me in withholding the work again. It’s come full circle to withholding the work again and only sharing it when I think it’s right. Asking questions of the publishing industry at large, making it more equitable for folks who are coming up.

Skyler: How do you think, well, obviously you are publishing more long form work, as of late, how do you think that defers from the poetry world?

Hanif: I mean it’s easier, I also stopped publishing as much long form work online. Last year I had like two columns, at once. I had to shut them down. Not shut them down but when they ended, I was like I can’t come back to this. Because again I was like, so much of my work is in the world all the time. What would it look like if I withheld some and offered up space to other people? One thing, it’s easier for long form work to get published or the process is quicker it’s not as – the thing that people don’t understand about poems is that, you’ll submit a poem in like January get it accepted in February but it might not come out until like, July. The process of publishing poetry is it always seems as though, because so many journals run on the same cycle if you get accepted by three and they all come out at once people are like woah, that person’s killing it, but it’s like nah, y’know that poem was accepted six months ago and that one was accepted eight months ago. So, there’s a way that just on its face, the traditional publishing model of poems is deceptive. It deceives people into imaging someone’s productivity being beyond what it actually is. Y’know I don’t know if that’s ideal.

Skyler: That is something I hadn’t considered before. Because I’ve always been told that there isn’t any money in poetry. You can’t have a career with poetry. But there’s obviously that ideology that if you get published in three different things then you’re killing it. So, what do you think is the driving force behind publishing? Why do we write –

Hanif: You write poetry?

Skyler: Yes!

Hanif: Well, for me, I can only speak for me, I think I don’t have any academic ambitions, because some folks have to be published in a certain amount of things for their C.V.s and whatnot. So, I don’t really have academic ambitions, I don’t really have any prestige ambitions. I don’t really care what journal I’m published in, though, don’t get me wrong, there was a point in my career where I absolutely did. But now I don’t really. Y’know for me, I really want to be where exciting work is happening. I read a lot of journals. I still read a lot of online poetry journals. If someone posts a poem to the internet and I like it, I trace it back to where it was originally published and read other work. Because for me, publishing gives me an opportunity to place my work next to more exciting work. to kind of build like an outer lineage of work that I’m proud of aside other exciting work. That’s kind of it. That’s how I make my publishing decisions now, where are the places – some of my not publishing poems also has to do with the fact that I’m finishing my next nonfiction project, I haven’t really written a lot of poems. But when I do start thinking about going back out with poems, the questions I’m asking are around the political alignment of a place and what kind of work they are putting out. Those two things are important to me.

Skyler: I do want to transition a little bit to talk about your long-form work, because I am biased, I do love poetry. But as you said, you are working on your next long-form work, could you tell me a bit more about that?

Hanif: It’ll be out in about a year, March 2021. Ideally. It’s a series of essays, though they don’t feel like essays, a series of long-form chapters about modes of black performance throughout US history. I got very interested in – I didn’t want to write a book about blackface, but I got very interested in this very concept of a country that does not mind profiting off the aesthetics of blackness as long as a black person isn’t attached. I honestly didn’t want to write about that on its face and I didn’t want to write about white people. So, I started thinking about very small modes of black performance that I think I don’t always celebrate as I should. I don’t know if you were at my reading but the thing I read about Wu-Tang and black men performing affection. There’s a thing about Josephine Baker and what it is to be from a place. There’s a thing about playing spades with my friends, y’know, these kinds of things that are untold or underappreciated and I wanted to kind of rhapsodize about them and give legs to the idea of black performance on its own as worthy of celebration.

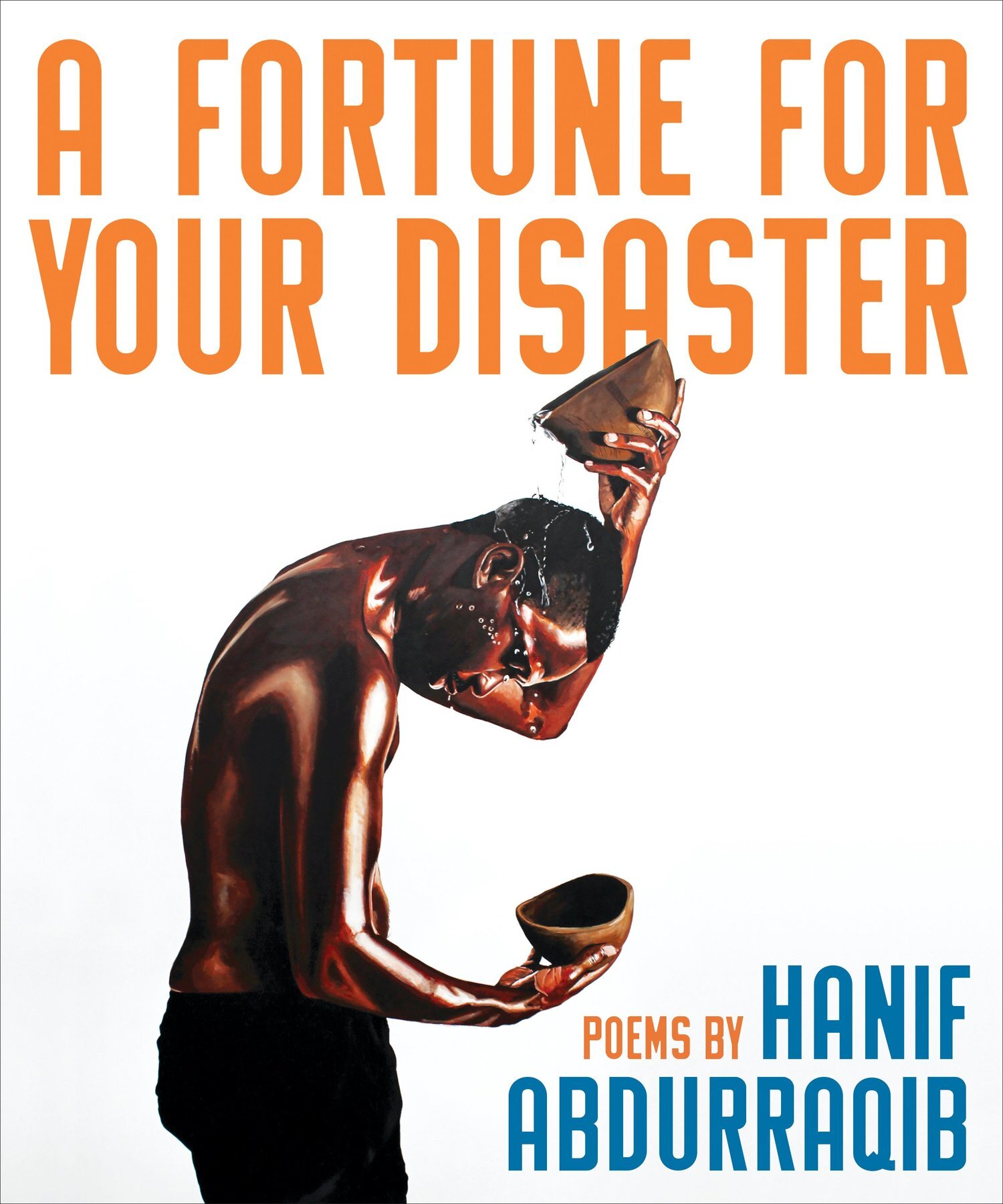

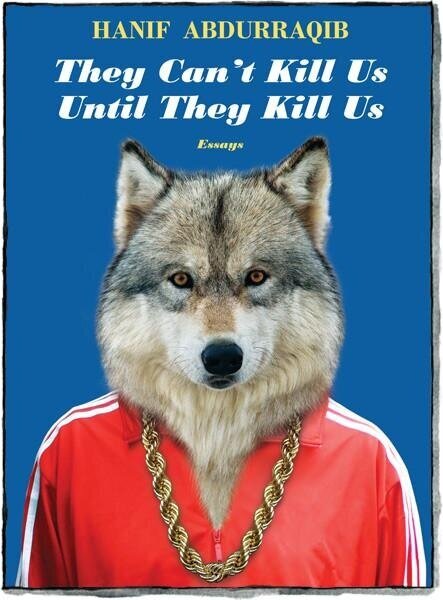

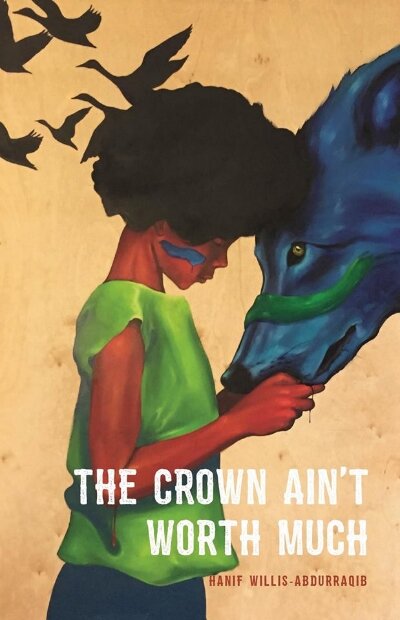

Skyler: I feel like I’ve seen that motif before in your other works like They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us. That uplifting of otherwise not looked upon things. Could you talk about how your third book follows in that trilogy, follows in the footsteps of your other two?

Hanif: Oh, the third nonfiction book? Well yeah, I think that for me this specifically is interesting to me, it’s interesting to uplift under-loved black performances or to detach those performances from the concept of how white people can consume those performances. That’s important to me. But in general, I like uplifting an under-told story, I like finding a well-known story and pushing it through a different lens, like I think in They Can’t Kill Us that happens a lot, like with the Fleetwood Mac thing and all that. I mean that excites me, it excites me to either share an exciting or a new story or push an old story through something new. A Tribe Called Quest book there were different modes I tried to do that with. It feels really rewarding to get to pull that off.

Skyler: Could you discuss, specifically, They Can’t Kill Us, and that MTV column you were writing, how that prepared you to write They Can’t Kill Us?

Hanif: Well I was already kind of prepared, I wrote nonfiction before I wrote poetry. I didn’t think of myself – it’s funny because when I got approached about writing an essay book, my first instinct was no. It was summer 2016 and my first poetry book had just come out. I kind of thought like this is it for me, I’ll write this book of poems and that’s what I got in me. I had been writing for MTV for maybe eight or nine months. I did have this body of work that seemed to be interrogating a lot of things. So, some of the work was just already there. So, if anything, writing for MTV prepared me because it allowed me to step back, take a look at my wider body of work, and identify the themes that I kept seeing. Much like the poems, when I first started writing poems, what kind of writing every week can bring up – allows me to say, oh, these are the themes that I’m chasing. So, to have a weekly column on MTV news, especially during that era, I know that our MTV news era wasn’t very long, but during that era where I was writing with folks like Doreen St. Felix and Molly Lambert and Ira Madison. I mean just like endless talented people; we were really pushing each other y’know. If I had to file something, if I had to file my column on a day that Doreen had something coming out I would always wait – everyone would do that actually, be like I’ll wait to see what Doreen wrote and then make sure my shit can rise to that level. We were in a kind of silent competition with each other, y’know we were pushing each other. Like if Molly dropped something, I’d sometimes push my column back a day. There’s nothing like writing alongside writers who’s taking their shit seriously. And that prepared me for that. When I was kind of holding my own in that kind of ecosystem, if I can do this, I can write a book.

Skyler: I feel like a lot of finding that good community depends on luck. I’m a senior now, this is my fourth year, and I feel like I just found that good community of people that I can share my work with and push each other with. So, I guess my question is when you don’t have that community, how do you push and motivate yourself and know when your work is good?

Hanif: Yeah, I don’t think it’s required. I don’t think having a community is required. I think it’s worked for me, but I think that there are a lot of folks who are averse to it and they do their work just fine. But, for me, there are many parts of my life now, because so much of my community of writers is disparate – they’re all over the place – and y’know we talk a lot, but there are a lot of us working in isolation. They Can’t Kill Us I wrote in isolation entirely. The parts that weren’t written I wrote in isolation. The way that I push myself, always, is just by asking myself – by pursuing work that I’m excited about. Pursuing curiosities that are exciting to me. That’s all the motivation I need. And to keep my head down and work. I always – people always talk about how much work I put out or whatever but it’s because I’m really really focused on the work. It is hard to get me to care about a lot of this other shit. By that I mean just like, I’m not very messy on the internet, I don’t think about award type stuff. I just do the work and from the work comes more work. That excites me more than anything.